Johannes Metellus

(1520 - 1597)

Metellus has one of the more mercurial biographies in the history of cartography. Born in Burgundy, he studied law under Andrea Alciat (1492–1556) at Bologna and, by 1552, appears to be employed assisting his fellow Burgundian Gilbert Cousin (1506–1572) with his Brevis ab dilucida Burgundiae Superioris, and in the publication of Lelio Torelli’s Encyclopaedia’(1553), and Benedict Aegius’s Apollori Athenensis Bibliothecas, sive de deorum origine (1555). After leaving Bologna, he travelled to Rome, Venice and Florence, England (in 1554), and Antwerp (where, it is presumed, he met Abraham Ortelius and Christophe Plantijn), before finally settling in Cologne at some time before 1563.

This date marks his earliest recorded correspondence from that town – a curious letter to the Flemish humanist and theologian George Cassander (1513–1566) on the medical applications of sasparilla (!).

Metellus is known to have contributed material to a new edition of Ortelius’s Theatrum in 1575, passed information to Gerard Mercator in 1577, concerning an expedition in Mexico and the spice trade in the East Indies, and he is thanked in the introduction to Michael Eitzinger’s Leo Belgicus. He also wrote the description of Lyon in the first volume of Braun and Hogenburg’s Civitatis Orbis Terrarum, and a preface to volume two of the same work. Whilst Metellus appears to have been of assistance to others, he was not, it would seem, particularly successful in getting his own output into print. The surviving works suggest that he planned ultimately to publish a small-format multi-volume world atlas, starting with France, Austria, and Switzerland (Meurer, MET1), and Spain (Meurer, MET2), although both of these were published anonymously.

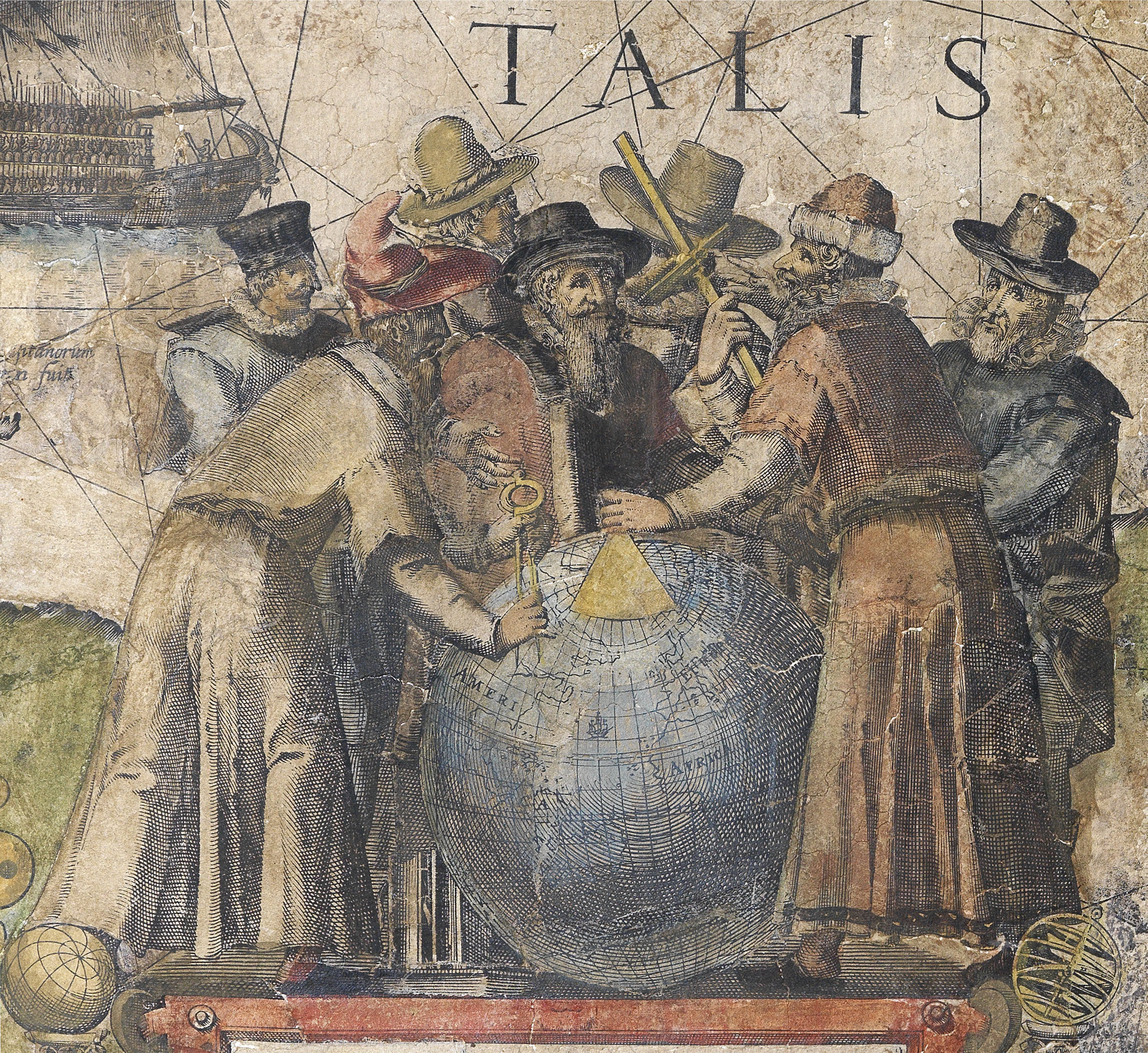

Metellus’ cartography is distinctive from the atlases produced in the Low Countries in the same period in that it borrows heavily from the Italian cartographic tradition of the so-called ‘Lafreri School’.

This is particularly evident in his final atlas, Insularum orbis aliquot insularum (1601), where at least half of the maps are not very well disguised copies of those of Giuseppe Rosaccio. This notwithstanding, the Insularum is an attractive publication and stands out as a northern European contribution to the tradition of “isolari”, or “island books’, that has its origins in the manuscript Mediterranean chart books of the fifteenth century, and in print with Bartolomeo dalli Sonetti, Bordone, and Porcacchi.

地图

地图  地图集

地图集  珍本

珍本  版画

版画  天文仪器

天文仪器