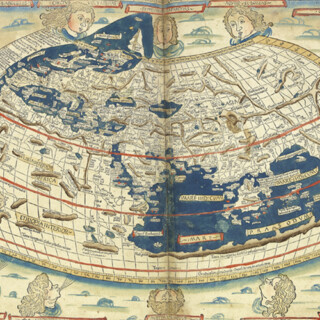

[a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);

Hua yi tu 華夷圖 (Map of the Chinese and non-Chinese).

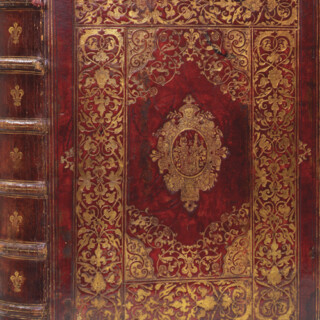

[c] Pingjiang tu 平江圖 (Map of Suzhou city).

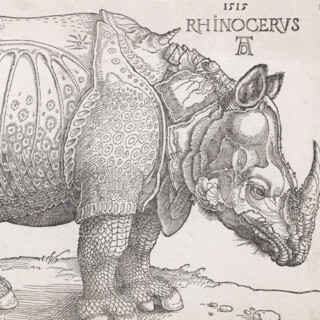

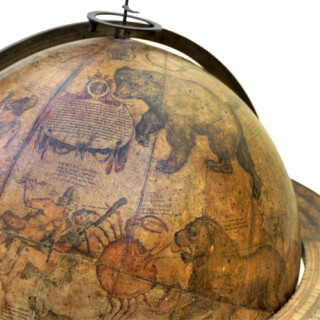

[d, e, f] Dili tu 墜理圖 (Geographic Map of China); Tianwen tu 天文 圖 (Map of the heavens); Diwang shaoyun tu 帝王紹運圖 (The chronological table of Emperors).

[a, b] Xi'an, c1900 [1136].

[c] Suzhou, [绍定二年, 1229]. [d, e, f] [Suzhou, 1247 but later].

[c] Suzhou, [绍定二年, 1229]. [d, e, f] [Suzhou, 1247 but later].

Ink rubbings from stone steles.

[a, b] 800 by 790mm (31.5 by 31 inches); 790 by 780mm (31 by 30.75 inches).

[c] 2680 by 1365mm (105.5 by 53.75 inches).

[d, e, f] 1790 by 960mm (70.5 by 37.75 inches); 1810 by 985mm (71.25 by 38.75 inches); 1830 by 965mm (72 by 38 inches).

[c] 2680 by 1365mm (105.5 by 53.75 inches).

[d, e, f] 1790 by 960mm (70.5 by 37.75 inches); 1810 by 985mm (71.25 by 38.75 inches); 1830 by 965mm (72 by 38 inches).

20503

notes:

A collection of six stone stele rubbings comprising the earliest geographically accurate map of China, the first urban plan made within the realm, and the oldest stone-engraved celestial map of the Chinese heavens.

The original engravings were made between 1136 and 1247 during the Southern Song dynasty. Together they represent a comprehensive study of ancient Chinese cartographical rubbings.

Among the earliest techniques in the art of Chinese cartograp...

The original engravings were made between 1136 and 1247 during the Southern Song dynasty. Together they represent a comprehensive study of ancient Chinese cartographical rubbings.

Among the earliest techniques in the art of Chinese cartograp...

bibliography:

De Weerdt, 'Maps and Memory: Readings of Cartography in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century Song China', 'The International Journal for the History of Cartography', volume 61, part 2, pages 145–167 (2020); Smith, 'Mapping China and Managing the World; Culture, Cartography and Cosmology in Late Imperial Times', pages 56–58 (2013).

provenance:

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_1H.jpg?fit=3500%2C3436&ssl=1)

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_2H.jpg?fit=3384%2C3500&ssl=1)

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_3H.jpg?fit=1873%2C3500&ssl=1)

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_4H.jpg?fit=1953%2C3500&ssl=1)

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_5H.jpg?fit=1991%2C3500&ssl=1)

![[a, b] ANONYMOUS [c] Li Shoupeng [d, e,f] [Wang Zhiyuan after Huang Shang] [a, b] Yu ji tu 禹跡圖(Map tracing the tracks of Yu the Great);](https://i0.wp.com/crouchrarebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/20503_6H.jpg?fit=1966%2C3500&ssl=1)