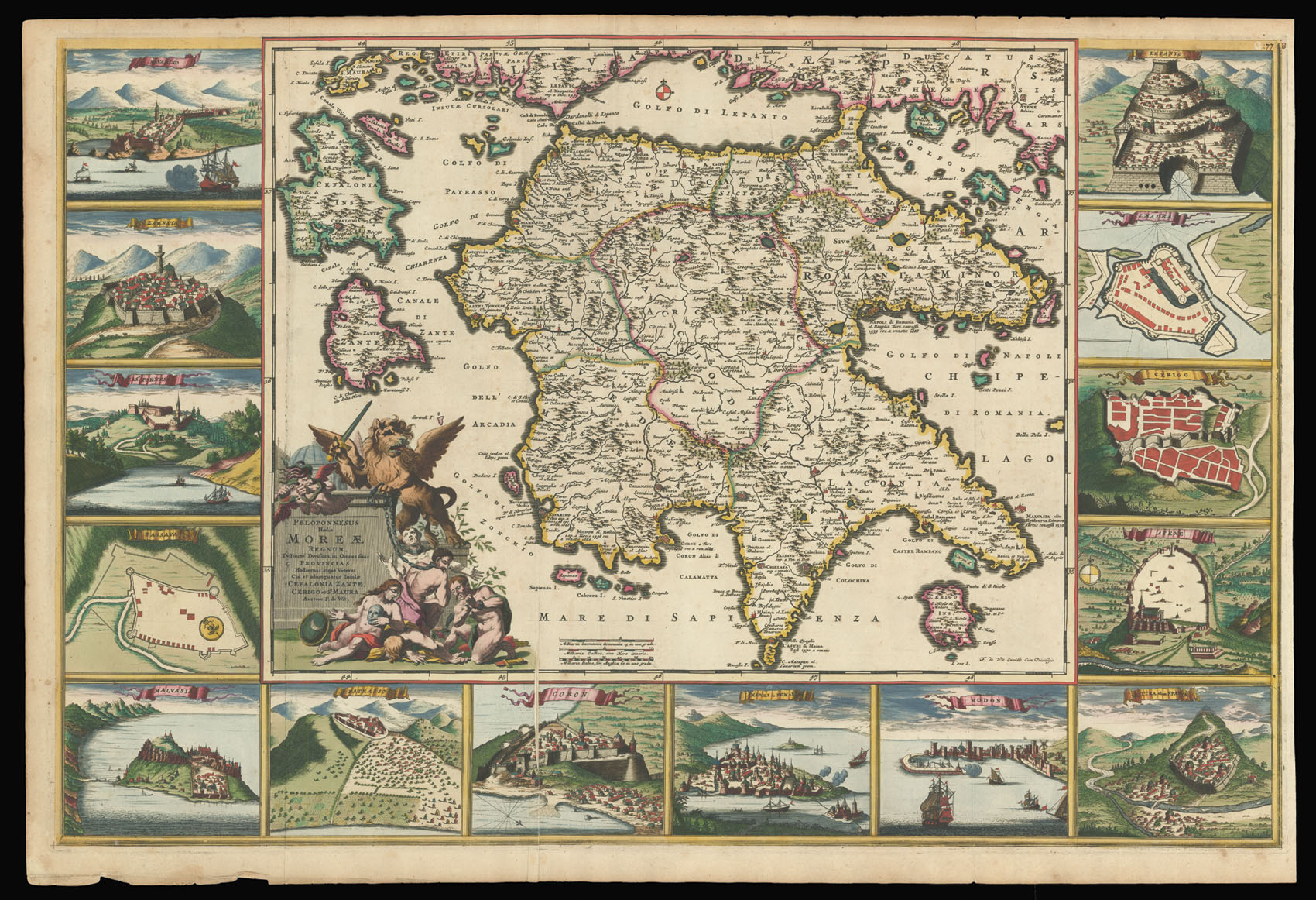

Peloponnesus Hodiae Moreae Peloponnesus Hodiae Moreae Distincte Divisum in Omnes suas Provincias, Hodiernas atque Veteres, Cui et adiunguntur Insulae Cefalonia, Zante, Cerigo et St. Maura Acore.

- Author: WIT, Frederick de

- Publication place: Amsterdam

- Publisher: Auctore F. de Wit

- Publication date: 1690.

- Physical description: First edition, first state. Large engraved map, 2 sheets joined (500 by 760mm to the neatline, full margins), with contemporary hand-colour in full. (Lower edge a little browned and beginning to fray near the left-hand corner).

- Dimensions: 535 by 795mm. (21 by 31.25 inches).

- Inventory reference: 12730

Notes

A spectacular map of Greece and surrounding islands, the first issue, with De Wit’s imprint. The title is within an elaborate allegorical cartouche lower left, showing the triumphant Venetian Lion of St. Mark subjugating Ottoman prisoners, in commemoration of the Serene Republic of Venice’s recent victories in the Sixth Ottoman – Venetian War, the “Great Turkish War”, in Morea or the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece.

The detailed map is surrounded by 14 vignettes of cities and castles, including: Navarino, Zarnata, Cas.l Tornes, Passava, Malvasia (now Monemvasia), Patrasso (Patrass), Coron (Korone), Napoli di Romania (Nafplio), Modon (Methoni), Misitra olam Sparta (Sparta), Atene (Athens), Cerigo (Kythira), S. Maura (Lefkada), and Lepanto.

When Frederick de Wit (1630-1706) moved to Amsterdam in 1648 he was already a well-established cartographic artist, engraving a plan of Haarlem around 1648 and providing city views for Antonius Sanderus’s “Flandria Illustrata”. He was apprenticed to Willem Blaeu, but by 1654 he had his own business, issuing his own map of the world, “Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula”, as both a wall map and a folio mapsheet in 1660. Two years later, he began to print atlases, the earliest of which were small compilations of prints from the stock of contemporaries. His later work included larger atlases of his own work. By the 1770s, de Wit was making atlases with over 150 maps.

More on this by Peter Dickson: Christos Zacharakis in the third edition (2009) of his monumental work, A Catalogue of Printed Maps of Greece 1477-1800 belatedly noted there was another version of this map which he indexes as 3710/2388 because of a significant difference. Zacharakis states that the fourth inset view on the left side of the map, which shows the castle or acropolis at Corinth, was replaced with a view of the floor plan for the castle at Passava located in the peninsula known as the Mani.

It turns out that Zacharakis was mistaken. The situation was the reverse which is easy to prove. And which, along with other notations, we can prove that De Wit made the map with Passava while the last Venetian-Ottoman War for control of the Peloponnese that began in 1684 was still underway.

The version which I purchased from Daniel Crouch last month has the view of Passava as the fourth inset image from the top on the left side of the map. But this same map does not contain revealing notations which I have seen on all other examples of De Wit’s map.

These notations state that Athens and Patras, along with two forts at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth known as Rion and Anti-Rion, had fallen to the Venetians in the summer of 1687. These other versions also note that the Turks had surrendered Monemvasia (Malavasi) known as the Greek Gibraltar to the Venetians. That actually happened in August 1690.

Thus, it stands to reason that the version which shows Passava and which does not show the aforesaid notations was made sometime in late 1686 or early 1687 because it does have notations for other castles that the Venetians captured in the summer of 1686.

If the Second State was an update made possibly not long after the fall of Monemvasia in August 1690, then the time lapse between the two versions was perhaps only 2 or 3 years. This might explain why all the other versions of this De Wit map I have been able to track down are of the Second State.

The removal of the image of Passava in the later version may have something to do with the apparent destruction of the castle during the later fighting. Danckerts also did not include it in his print showing 18 castles, forts and towns that he made circa 1690 — a rare print which I was also fortunate to purchase from Barry Ruderman last month.

Thus far, I have been able to locate in records the De Wit map being offered for sale only 10 times since the early 1980s, with two being resales — meaning 8 maps offered for sale, including the one that Sanderus in Belgium has had for sale for 3400 Euros. There may of course have been other sales/resales.

One last observation. Zacharakis seems to be mistaken in his list of atlases that he suggests contain this De Wit map because at the Library of Congress here in Washington I could not find it in a 1733 edition of Covens and Mortier’s Atlas Nouveau and also not in an 1682 Atlas by van Waesberger. The latter is not a surprise because this atlas came out before the conflict began in 1684. I took special care to check these volumes closely to be sure whether or not this map was included and I could never find it.

The fact that De Wit’s map I purchased from Daniel Crouch is silent about Patras’ fall to the Venetians in July 1687 and Athens likewise to them in late September 1687 strongly suggests that the First State may be found only in one Atlas made late 1686-early 1687 and that the print run was small due to a decision to hold off until the smoke cleared regarding the major events in this conflict in the Peloponnese which ended more or less in 1690.

Bibliography

- Zacharakis 2387.

Rare Maps

Rare Maps  Rare Atlases

Rare Atlases  Rare Books

Rare Books  Rare Prints

Rare Prints  Globes and Planetaria

Globes and Planetaria