ROGGEVEEN

The Roggeveen Family

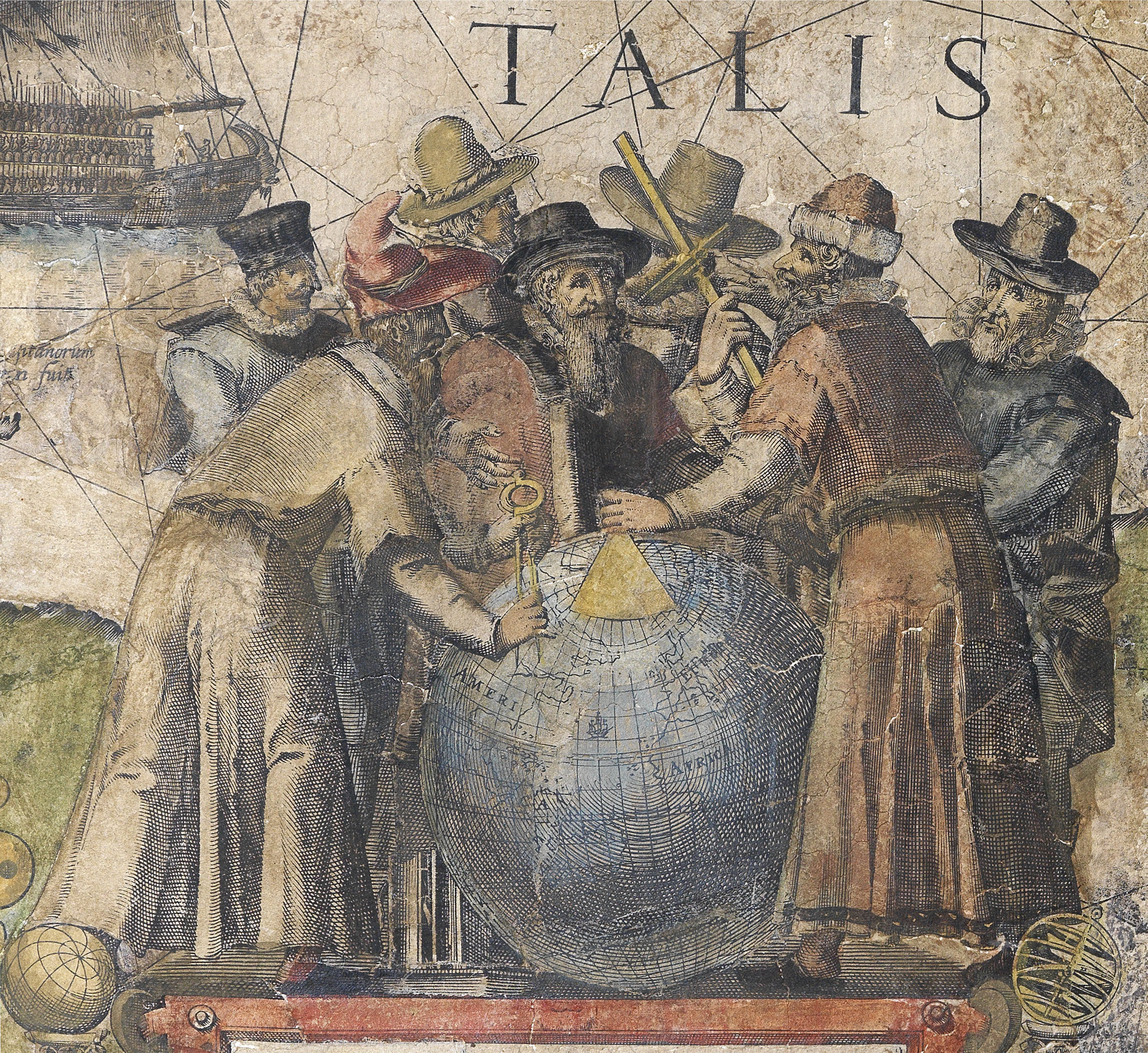

Arend (or Arent) Roggeveen (d1679) was a navigator and mapmaker. He moved to Middelburg in 1658, which at the time was the seat of both the Dutch West and East India Companies. He worked for both companies teaching navigation and overseeing their collection of maps and portolans. He began to create and compile charts of West Indies and North America in the 1660s, using the work of earlier cartographers including Hessel Gerritsz and Joan Vingboons. The collection was called Het Brandede Veen – The Burning Fen – a play on his name: fen was often used to create warning beacons on coasts for ships. This was the first pilot guide to show the entire coastline of North America on a large scale, and one of the first to name the island of Manhattan. It was published by Pieter Goos in 1675.

Jacob Roggeveen (1659-1729) was a Dutch explorer who set out to find Terra Australis. His father Arend had acquired an exploratory licence to search for Terra Australis from the States General in 1675. Arend died before he could accomplish his ambition, but his son Jacob would eventually make the journey.

Jacob Roggeveen worked as a notary in his hometown of Middleburg, and spent his later career in the East Indies, working as a member of the Council of Justice in Jakarta for the VOC. A controversial character, he was banned from Middleburg after he returned in 1714 for his support of liberal theological doctrines. In 1721, at the age of 62, Roggeveen submitted a proposal to the Dutch West India Company for an expedition to the Pacific to explore unknown areas of the company’s territory; essentially, like his father, looking for Terra Australis. Terra Australis was at this time known as Davis’s Land, after the land reportedly sighted by the English sailor Edward Davis in 1687. His brother, Jan, lobbied for support and provided financial assistance after the plan was approved. The expedition was comprised of three ships, and over 200 men.

The path of Roggeveen’s expedition took him past the Falkland Islands (which he renamed “Belgia Australis”), and around to Chile, where they stopped to make repairs and gather supplies. They then sailed over 1,500 miles across the Pacific Ocean, hoping to sight the coastline of the new continent on the other side. Instead, on Easter Sunday 1722, they sighted Easter Island, and became the first Europeans to set foot there. The ship’s log recorded the enormous stone idols which are still on the island, and thousands of people, before the inhabitants were wiped out by disease and slave raids.

After several other stops in the Pacific, losing one ship and half of the crew on the way, Roggeveen decided that the crew were too ill and too reduced in numbers to attempt to return via South America. He made the decision to sail around New Guinea, and the expedition limped into Batavia on 3 October 1722. They were promptly arrested by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the rival of the West India Company, for infringing their monopoly in the area. Their ships and property were confiscated and in 1723 he was returned to the Netherlands practically as a prisoner on the Company ships. Roggeveen was only compensated after several years of legal wrangling between the two Companies. In the confusion, however, Roggeveen’s journal of the voyage was lost. A copy made by VOC scribes in Batavia eventually surfaced in 1836, and it was published in 1838, providing a first-hand account of the expedition.

Rare Maps

Rare Maps  Rare Atlases

Rare Atlases  Rare Books

Rare Books  Rare Prints

Rare Prints  Globes and Planetaria

Globes and Planetaria