Louis-Charles Desnos

(

1725 - 1806

)

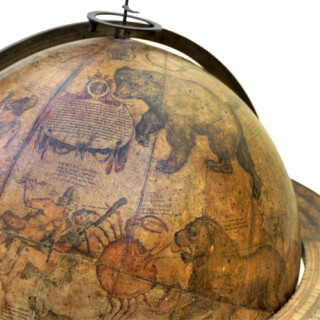

Although Louis-Charles Desnos lived and worked in Paris, he was appointed Royal Globemaker to Charles VII, King of Denmark. This may have had something to do with his acquiring the inventory of Jacques Hardy, whose son Nicolas’s widow he married. However, he did not stop short at globes: Desnos commissioned and sold maps, atlases, prints, screens, writing materials, and books. He acquired inventory from the Jaillot family and Nicolas de Fer, and worked extensively with other cartographers, particularly with Giovanni Rizzi-Zannoni, Claude Buy de Mornas, and Louis Brion de la Tour; sometimes fairly, sometimes in a rather underhand way.

There is no doubt that Louis-Charles Desnos was a sharp businessman, with an eye for opportunity. As early as 1750, Desnos announced plans to publish a fifteen-map historical geography of France illustrated with maps by Antonio Rizzi-Zannoni, which did not come to fruition, even though he seems to have later claimed that it had. If that had been true, then it would have been the earliest such atlas of France.

In 1761, Louis-Charles Desnos entered into a contract with Claude Buy de Mornas, to produce an Atlas méthodique et élémentaire de Géographie et d’Histoire (1761). Desnos’s investment in the Atlas… was three times the amount of Mornas’s. However, when Mornas was slow to provide the promised text for the work, Desnos pursued him for damages against having jeopardized the success of the venture and Desnos’s investment.

For his next big venture, Desnos decided to cut a few corners, and in 1763, the shoe was on the other foot, when Jean Lattre pursued Desnos for allegedly plagiarizing his Atlas maritime des Cotes de France (1762), reissuing it with maps by Rizzi-Zannoni. Desnos, at this point, was unphased by controversy, and compounded insult with injury by printing a version of Mme. Lattre’s map, Carte Helio-Seleno-Geographique,… (1762), showing the visibility of a solar eclipse, due to occur on the 1stof April, 1764, from different places in Europe. The Gendarmerie was summoned and seized an example of the Lattres’ map on Desnos’s premises. Desnos blamed Rizzi-Zannoni for everything, which was easy because Rizzi-Zannoni had in fact worked for and been paid for map designs by Lattre, without ever completing them. On the assumption that all publicity is good publicity, Desnos used the controversy to advertise his version of the map, claiming in the Journal de Trevoux, that Lattre’s accusations were defamatory, and offering his version of the map at less than half Lattre’s price.

Nevertheless, Desnos went some way to learning his lesson, and subsequent atlases acknowledged, as well as capitalized, on the success of others,… and were advertised as being useful for understanding well-known, best-selling histories. Desnos’s catalogue for 1765 lists three newly compiled historical atlases of France: Atlas historique et geographique de la France ancienne et moderne, after Messrs. Velly and Villaret, and Tableau analytique…, both prepared by Rizzi-Zannoni; Atlas historique, geographique et chronologique de la France ancienne et moderne, to complement Henault’s work, Abrege de l’histoire de France; and another atlas to accompany Daniel and Mezerai’s history of France.

True to old form, in 1766, Desnos published Rizzi-Zannoni’s maps from Brunet’s Abrege chronologique des grands fiefs (1759), without crediting him, as Atlas chronologique de la France … servant de supplement à l’atlas historique pour servir à la lecture de l’abŕegé chronologique de la reunion des grands fiefs.

Over his lifetime, Desnos’s output was prodigious, leading to the general accusation that he was not at all discerning – printing anything and everything that came his way.