“the principal cartographic authority on China during the eighteenth century”

Nouvel Atlas de la Chine, de la Tartarie Chinoise, et du Thibet

Contenant Les Cartes générales & particulieres de ces Pays, ainsi que la Carte du Royaume de Coree.

The Hague,

Henri Scheurleer,

1737

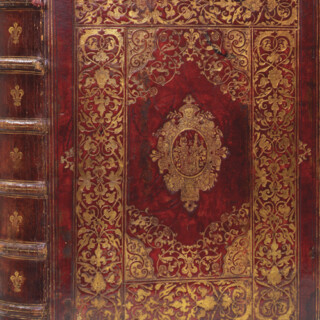

Folio (561 by 388mm), pp.12, 42 engraved maps, some folding, three hand-coloured in outline, contemporary blue paper boards, rebacked and corners with later half mottled calf gilt, morocco label.

14983

notes:

A rare atlas containing detailed maps of China's provinces, created to accompany Jean Baptiste du Halde's 'Description de la Chine'. Here, they have been issued as an atlas without du Halde's text. Du Halde, who became a Jesuit priest in 1708, was entrusted by his superiors to edit the published and manuscript accounts of Jesuit travellers in China. The finished work records the narratives of 27 of these missionaries, covering every aspect of Chinese society, from the langu...

bibliography:

A.H. Rowbotham, "The Impact of Confucianism on Seventeenth Century Europe", The Journal of Asian Studies 4 (1945).

provenance: