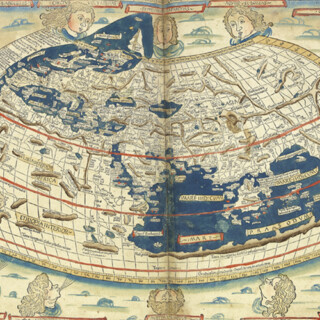

“The most spectacular contribution of the book-maker’s art to sixteenth-century science”

Astronomicum Caesareum.

Ingolstadt,

Peter Apian,

1540

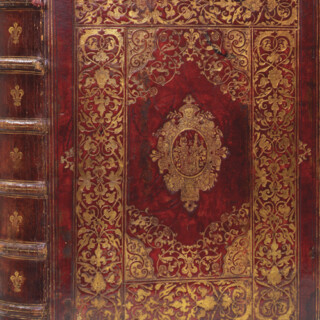

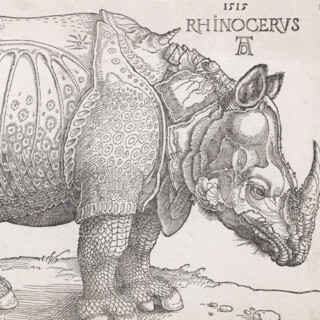

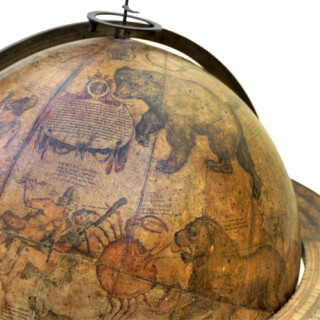

Folio (463 by 315mm). [59] ll., title-page framed by a woodcut border, on verso of the same leaf, woodcut coat of arms of the joint dedicatees Charles V and his brother Ferdinand of Spain, 53 11-line and 39 six-line historiated woodcut initials by Hans Brosamer, 36 full-page woodcut astronomical figures, of which 21 have a total of 83 volvelles [complete], 44 silk threads, 12 pearls, full original hand colour, full-page woodcut arms of the author by Michael Ostendorfer on fol. O6, small letterpress cancel slip on recto of fol. K1 correcting the text, contemporary German calf binding, tooled in blind with three rolls, one of half-length biblical figures, another, dated 1550, with classical heads in medallions, the third in conventional foliage, also a small took of a French type impressed in silver.

10777

notes:

First edition of "the most luxurious and intrinsically beautiful scientific book that has ever been produced" (de Solla Price, p.104), with wonderful original hand colour.

The author of this popular textbook in astronomy is Petrus Apianus. Petrus Apianus (1495-1552) was born in Saxony as Peter Bienewitz. He studied at the University of Leipzig from 1516 to 1519, where he took a Latinised version of his German name, Petrus Apianus. In 1527 the University of Ingols...

The author of this popular textbook in astronomy is Petrus Apianus. Petrus Apianus (1495-1552) was born in Saxony as Peter Bienewitz. He studied at the University of Leipzig from 1516 to 1519, where he took a Latinised version of his German name, Petrus Apianus. In 1527 the University of Ingols...

bibliography:

Adams A, 1277; Benezit II, 332 and VIII, 49; Campbell Dodgson II, 242; DSB I, pp.178-179; Lalande, p.60; Gingerich, 'A Survey of Apian's Astronomicum Caesareum', in Peter Apian, Karl Röttel (ed.), (Buxheim, 1995); Gingerich, Rara Astronomica, 14; Gingerich, 'Apianus's Astronomicum Caesareum', Journal for the History of Astronomy 2 (1971), pp.168-177; Kunitzsch, 'Peter Apian and 'Azophi''; Arabic Constellations in Renaissance Astronomy', in Journal for the History of Astronomy 18 (1987); Poulle, Les instruments de la théorie des planètes selon Ptolémée, (Genève, 1980) 1.83; Schottenloher, Landshuter Buchdrucker, 42; de Solla Price, Science since Babylon, (New Haven, 1975), p.1040; Stillwell, The Awakening Interest in Science during the First Century of Printing, 19; Van Ortroy, 112; Zinner 1734.

provenance:

Provenance

1. E.P. Goldschmidt (1887-1954), Sotheby's sale 24 November 1947, lot 95, Maggs, £250.

2. Major John Roland Abbey (1894-1969), initialled and dated acquisition note on rear-paste-down, Sotheby's sale 21 June 1965, lot 34, £1,200, Voisey.

1. E.P. Goldschmidt (1887-1954), Sotheby's sale 24 November 1947, lot 95, Maggs, £250.

2. Major John Roland Abbey (1894-1969), initialled and dated acquisition note on rear-paste-down, Sotheby's sale 21 June 1965, lot 34, £1,200, Voisey.